By Erik Sofge

Photographs by Chad Hunt

Published in the March 2009 issue of Popular Mechanics

When the US Special Forces need safe passage along a river, they call on the best-trained boatmen in the world. A PM reporter tags along on a live-fire exercise with the elite gunboat crews of Special Boat Team 22.

The First Gun to shoot doesn’t sound like a gun at all. The noise is high and buzzing, like a chain saw or a leaf blower. It stops, then starts up again. From my perch on the engine cover of a special operations gunboat, I can see the source of this weird racket—someone on one of the other boats gliding down Kentucky’s Salt River is firing a minigun into the woods. Every second, hundreds of 7.62 mm bullets pour out of the spinning machine-gun barrels. I’m pushing up my helmet, trying to spot the gunners’ targets, when someone close by yells “Contact,” and the boat I’m sitting in erupts in gunfire. Now the shell casings are landing in my lap as twin M240B machine guns rattle a couple of feet away. When the aft-mounted .50 caliber starts thumping, the pressure from each shot feels like a punch in the gut.

The First Gun to shoot doesn’t sound like a gun at all. The noise is high and buzzing, like a chain saw or a leaf blower. It stops, then starts up again. From my perch on the engine cover of a special operations gunboat, I can see the source of this weird racket—someone on one of the other boats gliding down Kentucky’s Salt River is firing a minigun into the woods. Every second, hundreds of 7.62 mm bullets pour out of the spinning machine-gun barrels. I’m pushing up my helmet, trying to spot the gunners’ targets, when someone close by yells “Contact,” and the boat I’m sitting in erupts in gunfire. Now the shell casings are landing in my lap as twin M240B machine guns rattle a couple of feet away. When the aft-mounted .50 caliber starts thumping, the pressure from each shot feels like a punch in the gut.

The volume of fire builds as two other Special Operations Craft-Riverine (SOC-R) boats join in, but no one is shooting back. This is a live-fire exercise at Fort Knox—and the thousands of rounds tearing through the air on this day are all outbound. The torrent of gunfire does not seem to rattle the members of Special Boat Team 22.

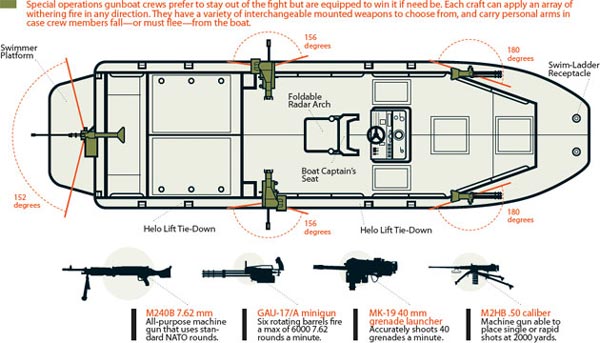

Many of these Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewmen, or SWCCs, have survived firefights along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in Iraq. Fast, heavily armed SOC-R boats are used mainly to insert or extract Navy SEALs, Army Rangers and other special forces personnel. If the enemy interferes, the SWCC response is, in military speak, “violence of action.” The SOC-R’s five weapon mounts provide a 360-degree field of fire. “Anyone who decides to shoot at us will immediately regret that decision once we start shooting back,” says Mike, my designated SWCC spokesman, his face patterned with green and black grease paint. “We have an overwhelming amount of firepower at our disposal. It’s pretty insane.”

A fog of gun smoke builds over the river as the boat crew fires, and when I inhale, the smoke burns the back of my throat. It’s no longer possible to make out the demolished targets or even the foliage on the river.

A fog of gun smoke builds over the river as the boat crew fires, and when I inhale, the smoke burns the back of my throat. It’s no longer possible to make out the demolished targets or even the foliage on the river.

This one-sided engagement has already covered the floor of the 33-ft-long boat with hundreds of spent casings. But the simulated fight isn’t over yet, even as the diesel engines throttle up and the boat speeds off. The aft gunner continues to rattle away on the .50-caliber, and clouds of dirt are still blooming on the offending bank.

Shadow Fighters

There’s a good reason SOC-R boats bristle with machine guns: Riverine craft fight in extremely close quarters. The enemy could be 20 yards away, crawling along the river’s edge. Other than the boat captain, who sits in a shielded compartment while driving, the crew is almost entirely exposed. A well-coordinated ambush could wipe them all out within seconds. Although SOC-R boats are highly maneuverable, avoiding a fight while on a narrow river isn’t always an option. “Your best defense is to shoot,” Mike says.

Members of Special Operations Forces (SOF) involved in fieldwork never release their full names to the press. SWCCs are in the same multibranch military family as Green Berets, Rangers and SEALs, and all are considered by the Pentagon to be “high-value targets,” meaning they could be personally targeted by the nation’s enemies. (Officials won’t say whether any SOF has ever been stalked in such a fashion.) During our live-fire ride-along, the restrictions on what we can describe extend to communications gear, the armor on the SOC-R hulls, tactical maneuvers and details of the boat-mounted sensors.

Members of Special Operations Forces (SOF) involved in fieldwork never release their full names to the press. SWCCs are in the same multibranch military family as Green Berets, Rangers and SEALs, and all are considered by the Pentagon to be “high-value targets,” meaning they could be personally targeted by the nation’s enemies. (Officials won’t say whether any SOF has ever been stalked in such a fashion.) During our live-fire ride-along, the restrictions on what we can describe extend to communications gear, the armor on the SOC-R hulls, tactical maneuvers and details of the boat-mounted sensors.

Special operations boat crews trace their heritage through Vietnam-era Swift boats back to the regular-Navy PT boats of World War II. Unlike those predecessors, SWCC units do not patrol, but instead train allied troops and participate in targeted raids. (The older units also didn’t parachute from transport airplanes with their boats, the way SWCCs do.)

Training is intense: Aspiring crewmen are expected to be able to perform 79 sit-ups in 2 minutes and swim 500 yards in 10 minutes. Their physical strength is needed to handle heavy gear—each crewman wears at least 70 pounds of ballistic protection, weapons, radios and medical gear—and also prevents injury. But physical conditioning doesn’t totally prevent back damage caused by the repeated impact of fast-moving boats slamming across waves. Many veteran SWCCs have scars from back surgeries made necessary by these shocks to their vertebrae.

The military won’t discuss specific SWCC missions, but it will say that SOC-R teams have faced heavy, regular action along the river systems of Iraq. “They’re out there, and they’re engaging,” says Rich Evans, Naval Special Warfare Group 4 command master chief. “There’s been a couple of missions that ended up in the largest firefights that guys on the water have been in since Vietnam.”

Since Sept. 11, 2001, the Special Forces have received an increasing share of personnel and funding—the SOF budget rose by more than 80 percent between 2001 and 2006. Evans says that the number of SWCCs is growing at a fast pace because of bureaucratic changes within the Defense Department. In 2006 the Pentagon changed the “source rating” of the SWCC’s units—the military equivalent of making a short-term civilian job into a permanent position. Now, “most guys who get into naval special warfare stay in,” Evans says. “They don’t go back to the fleet.”

The majority of the 650 total SWCC members, split into East and West Coast teams, conduct operations on coastal vessels (see page 82). Members of Team 22, based in Stennis, Miss., who make up a tiny fraction of the total SWCCs, are the only ones who operate the SOC-R. These river crews conduct mainly clandestine combat missions, often operating at night with little or no air support. Coastal teams, in contrast, spend more of their time these days training friendly international forces. “In the schoolhouse at SWCC school, you can choose which team you want to be on,” Mike says. “I specifically picked [Special Boat Team] 22, because it’s the most up-close-and-personal, aggressive team that the SWCCs have. I mean, you’re on a river, you’re a lot closer to any enemy; whereas, you know, it’s a huge ocean.”

America’s Most Heavily Armed Vehicle

The SOC-R wasn’t made to be versatile. Instead, it is a specialized tool built to help the SWCCs engage the enemy in tight surroundings—and prevail. The SWCCs told its builder, United States Marine, of Gulfport, Miss., that the craft could have a draft no deeper than 2 ft when fully loaded with armaments, ammunition, crew and passengers. It had to be compact enough to fit inside a C-130 military aircraft, narrow enough to slide through tight river passages and light enough to be hoisted by a Chinook helicopter. In Iraq, the helicopters sling these gunboats to lift them over dams, making possible an extra element of surprise.

Although the boat’s twin waterjets and 440-hp Yanmar diesel engines give it a hefty power-to-weight ratio, its speed and tight turn radius are facilitated by the hull design. The slope of the SOC-R’s V-shape belly essentially allows the boat to skate along the surface, with relatively little drag on the hull. There is no hanging rudder or propeller blades to snag on submerged roots and rocks.

Although the boat’s twin waterjets and 440-hp Yanmar diesel engines give it a hefty power-to-weight ratio, its speed and tight turn radius are facilitated by the hull design. The slope of the SOC-R’s V-shape belly essentially allows the boat to skate along the surface, with relatively little drag on the hull. There is no hanging rudder or propeller blades to snag on submerged roots and rocks.

The guns, however, are the SOC-R’s central attraction. Although tanks and light armored vehicles might have a more powerful cannon, there’s arguably more firepower per square inch here than on any other military vehicle.

The two forward weapon mounts of the boat I’m in are fitted with GAU-17/A miniguns. The electrically powered rotating barrels allow for bursts of up to 6000 rounds per minute. (Shooting at that rate through a single barrel could melt the weapon.) M240B light machine guns are fitted into the mid-mounts. Finally, the boat has an aft-mounted .50 cal that has the slowest output but the biggest punch—enough to penetrate light vehicle armor and most building materials. This weapon’s position is vital: It can cover the boat crews as they escape from an overwhelming threat.

Heavy Fire on Muddy Water

We’ve just simulated a “hot extract,” with the boat pushed up against a bank long enough for nonexistent passengers to scramble onboard. Other SOC-R teams provide covering fire—again, their targets disintegrate before I even have a chance to notice them. Chewing up entire swaths of riverfront property is a prelude to the getaway—our minifleet of SOC-Rs is on the run from the exfiltration site, .50 cals thumping away. “Sometimes on our special op missions, we just run away and come back and fight another day,” says Commodore Evin Thompson, former head of Naval Special Warfare Group 4, which runs the SWCCs.

With a series of bangs, a wall of smoke suddenly fills the river behind us. This is another trick the SOC-R crews can employ as they exit a fight—firing smoke canisters from four rear-facing launchers. “What’s interesting about the riverine environment is that if you get in trouble, you can either go up the river or down the river, not left or right,” Thompson says. On the way back, the flotilla pauses for an all-out exhibition—all four boats decimate a broad stretch of riverbank. Red tracer rounds streak through the dust kicked up by preceding shots, some of which chop lines along the water’s surface. With all boats firing, there are at least 12,000 rounds a minute coming at that bank.

With this part of the exercise over, most of the SWCCs head back to their trailer house for a break, but one boat gets the job of helping us with a photo op. The SOC-R speeds past a few times as we watch from the river bank, showing off how quickly it can come to a full stop. The crew’s last trick is a high-speed reverse: Everyone on board is cheering as the nimble craft whips its aft around 180 degrees, throwing one SWCC off balance. He manages to hold on before hitting the water, and his crewmates quickly pull him back. When we make it back to land, Mike is eager—and amused—to see the footage; he was the one who almost went overboard.

After ditching me and our photographer, the troop is getting ready to go out again. The sun has already slipped behind the tree line, but the crews still face a long session of overwhelming-firepower training ahead. Once it’s dark, they will run maneuvers, firing thousands more live rounds while wearing night-vision goggles.

After nearly 4 hours of daylight operations, the plan is to spend 8 to 12 more hours on the river. This is part of the final stretch of training before Mike’s group of roughly 50 SWCCs deploys to Iraq—by early spring, they may already be there. He wishes me luck as we part, and walks back toward the boats.

| Other Naval Special-Warfare Boats | |

| MK V Special Operations Craft | NSW Rigid Inflatable Boat |

|

|

| SEALs in a small inflatable boat can access these medium-range Mark Vs using a ramp on the stern. In addition to Special Operations Forces (SOF) delivery, Mark Vs are used to intercept and board enemy vessels and to launch unmanned aerial vehicles. | The primary mission of these extreme-weather craft is the short-range transport of SOF to and from enemy beaches. They also conduct recon and resupply. |

| Length: 81 ft 2 in. Max Speed: 48 knots Range: 500+ nautical miles Hull: Aluminum | Length: 36 ft 0 in. Max Speed: 45+ knots Range: 200+ nautical miles Hull: Glass-reinforced plastic with air-filled sponson |