The U.S. Navy SEALs were established by President John F. Kennedy in 1962 as a small, elite maritime military force to conduct Unconventional Warfare. They carry out the types of clandestine, small-unit, high-impact missions that large forces with high-profile platforms (such as ships, tanks, jets and submarines) cannot. SEALs also conduct essential on-the-ground Special Reconnaissance of critical targets for imminent strikes by larger conventional forces.

Birth of the Navy SEALs

SEALs are U.S. Special Operations Command’s force-of-choice among Navy, Army and Air Force Special Operations Forces (SOF) to conduct small-unit maritime military operations which originate from, and return to a river, ocean, swamp, delta or coastline. This littoral capability is more important now than ever in our history, as half the world’s infrastructure and population is located within one mile of an ocean or river. Of crucial importance, SEALs can negotiate shallow water areas such as the Persian Gulf coastline, where large ships and submarines are limited by depth.

The Navy SEALs are trained to operate in all the environments (Sea, Air and Land) for which they are named. SEALs are also prepared to operate in climate extremes of scorching desert, freezing Arctic, and humid jungle. The SEALs’ current pursuit of elusive, dangerous and high-priority terrorist targets has them operating in remote, mountainous regions of Afghanistan, and in cities torn by factional violence, such as Baghdad, Iraq. Historically, SEALs have always had “one foot in the water.” The reality today, however, is that they initiate lethal Direct Action strikes equally well from air and land.

WWII Origins

Today’s SEALs embody in a single force the heritage, missions, capabilities, and combat lessons-learned of five daring groups that no longer exist but were crucial to Allied Victory in World War II and the conflict in Korea. These were (Army) Scouts and (Navy) Raiders; Naval Combat Demolition Units (NCDUs), Office of trategic Services Operational Swimmers, Navy Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs), and Motor Torpedo Boat Squadrons.

These varied groups trained in the 1940s for urgent national security requirements, saw combat in Europe, North Africa, and the Pacific, but mostly disbanded after orld War II. However, The UDTs were called upon again and expanded quickly for the Korean War in 1950. Exercising great ingenuity and courage, these special maritime units devised and executed with relatively few casualties many of the missions, tactics, techniques and procedures that SEALs still perform today.

These missions included beach and hydro-reconnaissance, explosive cable and net cutting; explosive destruction of underwater obstacles to enable major amphibious landings; limpet mine attacks, submarine operations, and the locating and marking of mines for minesweepers. They also conducted river surveys and foreign military training. While doing this, the SEALs’ predecessors pioneered combat swimming, closed-circuit diving, underwater demolitions, and mini-submarine (dry and wet submersible) operations.

OSS Maritime Unit

Some of the earliest World War II predecessors of the SEALs were the Operational Swimmers of the Office of Strategic Services, or OSS. British Combined Operations veteran LCDR Wooley, of the Royal Navy, was placed in charge of the OSS Maritime Unit in June 1943. Their training started in November 1943 at Camp Pendleton, moved to Catalina Island in January 1944, and finally moved to the warmer waters in the Bahamas in March 1944. Within the U.S. military, they pioneered flexible swim fins and facemasks, closed-circuit diving equipment, the use of swimmer submersibles, and combat swimming and limpet mine attacks.

In May 1944, Colonel “Wild Bill” Donovan, the head of the OSS, divided the unit into groups. He loaned Group 1, under LT Choate, to ADM Nimitz, as a way to introduce the OSS into the Pacific Theater. They became part of UDT-10 in July 1944. Five OSS men participated in the very first UDT submarine operation with the USS BURRFISH in the Caroline Islands in August 1944

Scouts and Raiders

To meet the need for a beach reconnaissance force, selected Army and Navy personnel assembled at Amphibious Training Base, Little Creek, on 15 August 1942 to begin Amphibious Scouts and Raiders (Joint) training. The Scouts and Raiders mission was to identify and reconnoiter the objective beach, maintain a position on the designated beach prior to a landing and guide the assault waves to the landing beach.

The first group included Phil H. Bucklew, the “Father of Naval Special Warfare,” after whom the Naval Special Warfare Center is named. Commissioned in October 1942, this group saw combat in November 1942 during OPERATION TORCH, the first allied landings in Europe, on the North African coast. Scouts and Raiders also supported landings in Sicily, Salerno, Anzio, Normandy, and southern France.

A second group of Scouts and Raiders, code-named Special Service Unit #1, was established on July 7, 1943, as a joint and combined operations force. The first mission, in September 1943, was at Finschafen on New Guinea. Later ops were at Gasmata, Arawe, Cape Gloucester, and the East and South coast of New Britain, all without any loss of personnel. Conflicts arose over operational matters, and all non-Navy personnel were reassigned. The unit, renamed 7th Amphibious Scouts, received a new mission, to go ashore with the assault boats, buoy channels, erect markers for the incoming craft, handle casualties, take offshore soundings, blow up beach obstacles and maintain voice communications linking the troops ashore, incoming boats and nearby ships. The 7th Amphibious Scouts conducted operations in the Pacific for the duration of the conflict, participating in more than 40 landings.

The third Scout and Raiders organization operated in China. Scouts and Raiders were deployed to fight with the Sino-American Cooperation

Organization, or SACO. To help bolster the work of SACO, Admiral Ernest J. King ordered that 120 officers and 900 men be trained for “Amphibious Roger” at the Scout and Ranger school at Ft. Pierce, FL. They formed the core of what was envisioned as a “guerrilla amphibious organization of Americans and Chinese operating from coastal waters, lakes and rivers employing small steamers and sampans.” While most Amphibious Roger forces remained at Camp Knox in Calcutta, three of the groups saw active service. They conducted a survey of the Upper Yangtze River in the spring of 1945 and, disguised as coolies, conducted a detailed three-month survey of the Chinese coast from Shanghai to Kitchioh Wan, near Hong Kong.

Naval Combat Demolition Unit (NCDU)

In September of 1942, 17 Navy salvage personnel arrived at ATB Little Creek, VA for a one-week concentrated course on demolitions, explosive cable cutting and commando raiding techniques. On 10 November 1942, this first combat demolition unit succeeded in cutting a cable and net barrier across the Wadi Sebou River during Operation TORCH in North Africa. Their actions enabled the USS DALLAS (DD 199) to traverse the river and insert U.S. Rangers who captured the Port Lyautey airdrome.

Plans for a massive cross-channel invasion of Europe had begun and intelligence indicated that the Germans were placing extensive underwater obstacles on the beaches at Normandy. On 7 May 1943, LCDR Draper L. Kauffman, “The Father of Naval Combat Demolition,” was directed to set up a school and train people to eliminate obstacles on an enemy-held beach prior to an invasion.

On 6 June 1943, LCDR Kaufmann established Naval Combat Demolition Unit training at Ft. Pierce, Florida. Most of Kauffman’s volunteers came from the Navy’s engineering and construction battalions. Training commenced with one grueling week designed to eliminate the men from the boys. Some said that the men had sense enough to quit, and left the boys. It was and is still considered “HELL WEEK”.

The training made the use of rubber boats and surprisingly little swimming. The assumptions were that the men would paddle in and work in shallow water leaving the deep-water demolitions to the Army. At this point, the men were required to wear Navy fatigues with shoes and helmets. They were ordered to be life-lined to their boats and stay out of the water as much as possible. Kauffman’s experience was at disarming explosives, now he and his teams were learning to use them offensively. One innovation was to use 2.5-pound packs of tetryl paced into rubber tubes, thus making 20 pound lengths of explosive tube that could be manipulated around obstacles for demolition.

By April 1944, a total of 34 NCDUs were deployed to England in preparation for Operation OVERLORD, the amphibious landing at Normandy.

Tested in combat: Normandy D-Day invasion

Six men from Kauffmans Naval Combat Demolition Unit Eleven (NCDU-11) were sent to England in the beginning of November 1943 to start preparations to clear the beaches for the Normandy invasion. Later NCDU 11 was enlarged into 13 man assault teams. The Scouts and Raiders were also deployed to start their recon of the Normandy Coast.

Six men from Kauffmans Naval Combat Demolition Unit Eleven (NCDU-11) were sent to England in the beginning of November 1943 to start preparations to clear the beaches for the Normandy invasion. Later NCDU 11 was enlarged into 13 man assault teams. The Scouts and Raiders were also deployed to start their recon of the Normandy Coast.

General Rommel, Hitler’s greatest military Field Marshal, had implemented the intricate defenses found on the French coastline. These creatively included steel posts driven into the sand and topped with explosives. Large 3-ton steel barricades called Belgian Gates were placed well into the surf zone. Additionally, he strategically placed reinforced mortar and machine gun nests. The Scouts and Raiders spent weeks gathering information during nightly surveillance missions up and down the French coast. Replicas of the Belgian gates were constructed on the South Coast of England for the UDT to practice demolitions on. The strategy of the UDT was to knock the gates flat, not to shred and spread them along the beaches, thereby creating more of an obstacle for the advancing troops.

Men armed with naval offshore artillery, which included bombs and shells, led the initial attack on the two American landing beaches of Omaha & Utah. Then a first wave of tanks and troop carriers were to land and clear any remaining German bunkers and snipers. The Demolitions Gap-assault teams would come in with the second wave and work at low tide to clear the obstacles.

As happens often during the fog of war, the Allied aircraft ended up dropping their bombs too far inland. Navy artillery then sent the majority of their shells far over the German positions – wreaking havoc on the French farmlands but leaving the well-positioned German guns in perfect operating condition. These guns sent withering ground fire against the approaching Allied forces. The tides also ended up pushing many of the demolition crews well ahead of the first wave. They found themselves the first to land on the beaches. Many of the teams were killed by machine gun and mortar fire before reaching the beach. Other team members under enemy fire managed to set charges on the obstacles and blow them. At one point, soldiers were taking cover behind the obstacles, which were emplaced with demolitions charged with timers. The GIs quickly made their way onto the beaches to avoid becoming a friendly casualty of war. The mission was to open sixteen 50-foot wide corridors for the landing. By nightfall only thirteen were open, and these beaches exacted a heavy toll on the Navy Gap-Assault teams.

Of the 175 NCDU and UDT men on Omaha beach, 31 where killed and 60 wounded. Their Teammates on Utah Beach faired far better because the beach was considerably less fortified. Four were killed and11 wounded, when an artillery shell landed among one of the teams working to clear the beach. Weeks before the invasion all available Underwater Demolition men were sent from Fort Pierce to England. The largest loss occurred at the landing on Omaha beach, Normandy. Within months of the War’s end, the UDT teams were dispersed. This ended a trying but evolutionary time in the history of Naval Special Warfare.

On 6 June 1944, in the face of great adversity, the NCDUs at Omaha Beach managed to blow eight complete gaps and two partial gaps in the German defenses. The NCDUs suffered 31 killed and 60 wounded, a casualty rate of 52%. Meanwhile, the NCDUs at Utah Beach met less intense enemy fire. They cleared 700 yards of beach in two hours, another 900 yards by the afternoon. Casualties at Utah Beach were significantly lighter with 6 killed and 11 wounded. During Operation OVERLORD, not a single demolitioneer was lost to improper handling of explosives.

In August 1944, NCDUs from Utah Beach participated in the landings in southern France, the last amphibious operation in the European Theater of Operations. NCDUs also operated in the Pacific theater. NCDU 2, under LTjg Frank Kaine, after whom the Naval Special Warfare Command building is named, and NCDU 3 under LTjg Lloyd Anderson, formed the nucleus of six NCDUs that served with the Seventh Amphibious Force tasked with clearing boat channels after the landings from Biak to Borneo..

The South Pacific – Growth of UDT

After a major catastrophe on the island of Tarawa, the need for the UDT in the South Pacific became glaringly clear. The islands in this region have unpredictable tide changes and shallow reefs that can easily thwart the progress of the naval transport vessels. At Tarawa, the first wave made it across the reef in Amtracs, but the second wave in Higgens boats got stuck on a reef left exposed by the low tide. The Marines had to unload and wade to shore. Many drowned or were killed before making the beach. The Amtracs, without reinforcements from the second wave, were slaughtered on the beach. It was a valuable lesson that the Navy would not permit to be repeated. The Navy Combat Swimmers were turned to for an answer.

After a major catastrophe on the island of Tarawa, the need for the UDT in the South Pacific became glaringly clear. The islands in this region have unpredictable tide changes and shallow reefs that can easily thwart the progress of the naval transport vessels. At Tarawa, the first wave made it across the reef in Amtracs, but the second wave in Higgens boats got stuck on a reef left exposed by the low tide. The Marines had to unload and wade to shore. Many drowned or were killed before making the beach. The Amtracs, without reinforcements from the second wave, were slaughtered on the beach. It was a valuable lesson that the Navy would not permit to be repeated. The Navy Combat Swimmers were turned to for an answer.

The Fifth Amphibious Force set up training at Waimanalo, on the coast of Oahu in the Hawaiian Islands. Attending were men from Fort Pierce as well as men from the Army and Marines. Represented were the Scouts and Raiders as well as the Naval Combat Demolitions Teams. They hastily trained for the attack on Kwajalein on 31 January 1944. This was a major turning point for the tactics of the UDT. The plan was to send in night reconnaissance teams such as the Scouts and Raiders were accustomed to. Then Admiral Turner, worried about the presence of obstacles emplaced by the Japanese, ordered two daylight recon operations.

The missions were to follow the standard procedure. Team one was to go in a rubber boat in full fatigues, boots, life jackets and metal helmets. The coral reef kept their craft too far from shore to be certain of the beach conditions. Ensign Lewis F. Luehrs and Chief Bill Acheson made a decision that changed the shape of Naval Special Warfare forever. Removing all but their underwear, they swam undeterred across the reef. They returned with sketches of the beach gun embankment locations, along with information about a log wall built to deter landings and other vital intelligence. Naval Combat Swimming had now entered onto the Mission Essential Task List of the UDT.

After Kwajalein, the UDT created the Naval Combat Demolition Training and Experimental Base on Maui. Operations began in April 1944. Most of the procedures from Fort Pierce had been modified, with importance placed upon developing strong swimmers. Extensive training was conducted in the water without lifelines, using facemasks and wearing swim trunks and shoes in the water. This new model gave us the image that stands today of the WWII UDT “Naked Warrior”. The landings continued and at Iwo Jima the surveying teams fared favorably. The largest casualties of the UDT occurred not in the water, but aboard the destroyer USS Blessman when a Japanese bomber hit it. When the bomb exploded in the mess hall, fifteen men on the UDT Team were killed. Twenty-three others were injured. This was by far the most tragic loss of life suffered by the UDT in the Pacific theater.

Up until now all the islands worked upon were in southern waters. Soon the forces moved North toward Japan. Having no thermal protection, the UDT men were at risk of hypothermia and severe cramps. This problem was extreme during the surveying of Okinawa. The largest UDT deployment in the war employed veteran Team’s Seven, Twelve, Thirteen, Fourteen and newly trained teams Eleven, Sixteen, Seventeen, and Eighteen. Close to a thousand UDT forces worked in concert on operations both real and deceptive to create the illusion of landing in other locations. Pointed poles set into the coral reef of the beach protected the landing beaches on Okinawa. Team’s Eleven and Sixteen were sent in to blast the poles. After all the charges were set, the men swam to clear the area and the following explosion took out all of Team Eleven’s and half of team Sixteen’s targets. Team Sixteen broke from the operation due to the death of one of their men; hence, their mission was considered a failure and a disgrace. Team Eleven was sent back the following day to finish the job and then remained to guide the forces to the beach. The UDT continued to prepare for the invasion of Japan. After the atomic bomb exploded over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the war quickly ended. The need for an invasion of Japan was averted and the UDT’s role in the South Pacific came to an end.

All told 34 UDT teams were established. Wearing swim suits, fins, and facemasks on combat operations, these “Naked Warriors” saw action across the Pacific in every major amphibious landing including: Eniwetok, Saipan, Guam, Tinian, Angaur, Ulithi, Pelilui, Leyte, Lingayen Gulf, Zambales, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Labuan, Brunei Bay, and on 4 July 1945 at Balikpapan on Borneo which was the last UDT demolition operation of the war. The rapid demobilization at the conclusion of the war reduced the number of active duty UDTs to two on each coast with a complement of 7 officers and 45 enlisted men each.

China

An Annapolis graduate, named Milton E. Miles, once lived in China and knew how to speak the language. He was sent there to do anything in his power to prepare for an Allied landing in China. Although the landings were never conducted, Miles proved a great disturbance to the Japanese occupied regions of China. He set up a valuable chain of surveillance along eight hundred miles of the coast. He also formed a guerilla training camp called “Happy Valley” in conjunction with a Chinese warlord. From Happy Valley, they commanded many successful raids and guerilla warfare forays against the Japanese. Another UDT man, Phil Buckelew, also spent time under cover on Mainland China disrupting enemy lines of communication and providing intelligence to Naval commanders. The Philip Buckelew Naval Special Warfare Center in Coronado, California is named for this legendary man.

UDT in Korea

The Korean War began on 25 June 1950, when the North Korean army invaded South Korea. Beginning with a detachment of 11 personnel from UDT 3, UDT participation expanded to three teams with a combined strength of 300 men.

During the “forgotten war” the Underwater Demolition Teams fought heroically and with little fanfare. The UDT started to employ demolition expertise gained from WWII and adapt it to an offensive role. Continuing the effective use of the water as cover and concealment as well as a method of insertion, the Korean Era UDT targeted bridges, tunnels, fishing nets and other maritime and coastal targets. They also developed a close working relationship with the Republic of Korea (ROK) UDT/SEALs, whom they trained, which continues to this day.

The UDT refined and developed their commando tactics during the Korean War, with their efforts initially focused on demolitions and mine disposal. Additionally, the UDT accompanied South Korean commandos on raids in the North to demo train tunnels. The higher-ranking officers of the UDT frowned upon this activity because it was a non-traditional use of the Naval forces, which took them too far from the water line. Due to the nature of the war, the UDT maintained a low operational profile. Some of the better-known missions include the transport of spies into North Korea and the destruction of North Korean Fishing nets used to supply the North Korean Army with several tons of fish annually.

As part of the Special Operations Group, or SOG, UDTs successfully conducted demolition raids on railroad tunnels and bridges along the Korean coast. On 15 September 1950, UDTs supported Operation CHROMITE, the Amphibious landing at Inchon. UDT 1 and 3 provided personnel who went in ahead of the landing craft, scouting mud flats, marking low points in the channel, clearing fouled propellers, and searching for mines. Four UDT personnel acted as wave-guides for the Marine landing.

In October 1950, UDTs supported mine-clearing operations in Wonsan Harbor where frogmen would locate and mark mines for minesweepers. On 12 October 1950, two U.S. minesweepers hit mines and sank. UDTs rescued 25 sailors. The next day, William Giannotti conducted the first U.S. combat operation using an “aqualung” when he dove on the USS PLEDGE.

For the remainder of the war, UDTs conducted beach and river reconnaissance, infiltrated guerrillas behind the lines from sea, continued mine sweeping operations, and participated in Operation FISHNET, which severely damaged the North Korean fishing capability.

The Korean War was a period of transition for the men of the UDT. They tested their previous limits and defined new parameters for their special style of warfare. These new techniques and expanded horizons positioned the UDT well to assume an even broader role as the storms of war began brewing to the South in the Vietnamese Peninsula.

Vietnam ramps up – SEAL Teams formed

In 1962, President Kennedy established SEAL Teams ONE and TWO from the existing UDT Teams to develop a Navy Unconventional Warfare capability. The Navy SEAL Teams were designed as the maritime counterpart to the Army Special Forces “Green Berets.” They deployed immediately to Vietnam to operate in the deltas and thousands of rivers and canals in Vietnam, and effectively disrupted the enemy’s maritime lines of communication.

The SEAL Teams’ mission was to conduct counter guerilla warfare and clandestine maritime operations. Initially, SEALs advised and trained Vietnamese forces, such as the LDNN (Vietnamese SEALs). Later in the war, SEALs conducted nighttime Direct Action missions such as ambushes and raids to capture prisoners of high intelligence value.

The SEALs were so effective that the enemy named them, “the men with the green faces.” At the war’s height, eight SEAL platoons were in Vietnam on a continuing rotational basis. The last SEAL platoon departed Vietnam in 1971, and the last SEAL advisor in 1973.

Early colonial period

The French colonized Vietnam in 1857. They made it a part of French Indochina until World War II, when it fell under Japanese rule for a short time. Vietnamese citizens rebelled during the period of Japanese rule, supported by the Communists and American OSS (Office of Strategic Services which was the pre-cursor to the CIA). A new sense of nationalism emerged amongst the Vietnamese. World War II became the catalyst for the nationalist movement, which was led by a man calling himself Ho Chi Mihn.

After the war, France returned and sought to resume control of Vietnam and other Japanese-controlled territories. As early as 1941, Indochina’s Communist Party called for liberation from France. The Viet Mihn, the nationalist movement’s political and military organization, under the leadership of Ho Chi Mihn, were gaining strength in the north. In 1945 Ho Chi Mihn proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam and right for the Vietnamese to rule themselves. Their Declaration of Independence was written to be similar to the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776, hoping to gain support and sympathy from their one-time ally, America.

Elections that followed were strongly in favor of the Viet Mihn position. Ho Chi Mihn was proclaimed President of the new Republic and he demanded the immediate withdrawal of the French and complete independence for Vietnam. Ho Chi Mihn made these demands, relying on the support and aid he was receiving from two important sources: the Communist Chinese, and the American OSS Teams. The Communist Chinese trained the Viet Mihn and fought with them against the Japanese. The American OSS was advising Ho Chi Mihn in their common struggle against the Japanese. The United States government realized that the Viet Mihn was an effective fighting force and Ho Chi Mihn’s organization was the only stable leadership in Vietnam.

With the Chinese and OSS supporting Ho Chi Mihn, France found it difficult to oppose his new Republic. By late 1945, the OSS Teams were finally withdrawn and the French agreed to recognize the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam as long as it remained part of France. The French also agreed that if some time in the future the country wanted to unite under Ho Chi Mihn, France would submit to the decision of the people.

However, negotiations failed when neither side was willing to make any real compromise. Armed confrontations began between French Troops and the Viet Mihn, now called the National Front. The country of Vietnam divided: Ho Chi Mihn consolidated to the north in Hanoi, while the French set up government and command in the south at Saigon.

The French, with their Vietnamese allies, fought against the Viet Mihn from 1946 to 1953. This war consisted mostly of guerrilla actions, leaving neither side with a clear advantage. France’s military policy was not effective against guerrilla tactics, and the best the French could do was to hold the primary populated areas and main lines of communication, hoping to draw the Viet Mihn into a major action. The French were suffering heavy losses and casualties and needed a major win. They believed that if they were to get the Viet Mihn onto a conventional field of battle, France would have the upper hand.

The trap was set in a small valley in northwestern Vietnam, which was believed to be a guerrilla power base, about 150 miles west of Hanoi and 25 miles from the Laotian border. Under the control of General Henri Navarre, the French troops planned to lure the Viet Mihn into battle with a large airborne assault force, which would secure the valley and establish a fortification around the deserted airfield there. When the Viet Mihn attacked, the French would destroy them.

Dien Bien Phu became one of the greatest post-WWII battles. The French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu because they greatly underestimated the determination and abilities of the Vietnamese guerrilla forces. The French fortifications were insufficient; they were out manned, outgunned, and outmaneuvered. Neither the bravery of the French troops, nor the legendary heroics of the French Foreign Legion paratroopers, were enough to save the situation. This defeat shocked the French people and their government, eliminating their will to continue the war.

In July 1954, talks between France and the new Republic, held in Geneva, finally produced an agreement. The Geneva Agreement ended colonial rule in Vietnam with a working plan for the smooth transition of power from the French to the Vietnamese. The agreement divided Indochina into four parts: Laos, Cambodia, and North and South Vietnam. The ardently Communist Viet Mihn, lead by Ho Chi Mihn, ruled the North, while the French assisted in the establishment of an anti-communist Vietnamese government in the South, headed by Emperor Bao Dai.

With the northern region being the industrial center, and the southern regions being agricultural, the division of Vietnam posed economic problems. This division also caused a major shift in population. The large Catholic population in the North, fearing retaliation from the new Communist regime for their support of the French began an exodus to the South. An estimated 100,000 of the Viet Mihn stationed throughout the South, by order of the Hanoi government, began their own exodus to the North. However, at least 5,000 of their ranks remained behind, joining the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam to form the Viet Cong (VC). They lived in the South Vietnamese villages and fought against the American-funded ARVN (Army of the Republic of Viet Nam) and American troops.

Ho Chi Mihn was confident that he would win the elections, and turned his attention toward the economic and social troubles facing his government. He realized that the U.S. might aid the South in its establishment, but he did not foresee that South Vietnam would find grounds to cancel the elections. The Americans supported the Premier of South Vietnam, Ngo Dihn Diem, who replaced the self-exiled Bao Dai. Ngo Dihn Diem gradually increased his sphere of power, while the United States began to assume the role of supporter left vacant by the French.

America gets involved

Cambodia was the only state involved which refused to sign the Geneva Agreement; it was self-declared neutral and led by Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

Although Cambodia tried to play all sides against one another, the war didn’t lead into Cambodia until later years Laos, whose leader was Prince Souvanna Phouma, tried to develop a neutralist coalition government of both pro-Western and pro- Communist supporters. Prince Phouma’s half-brother Prince Souphanouvoing headed the Communist faction, called the Pathet Lao. Prince Boun Oum had the support of the 25,000-man Royal Laotian Army (RLA); the RLA led the pro-Western faction, and the United States Government supported it in order to counter a growing Communist presence in Asia.

Each faction actively tried to gain an advantage in the government. The 1958 elections gave the Pathet Lao more votes and the U.S. put pressure on Souvanna Phouma to resign in favor of the American-backed, Phoui Sananikone, who would continue the neutralist policy. This support from the United States was offensive to many. A young captain, Kong Le, who commanded the paratroop battalion of the RLA, seized the Laos capital, Vientiane, demanding a return to the neutralist policies.

The Soviet Union began sending arms, vehicles, and antiaircraft to Kong Le’s forces, while the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) sent cadres to train the troops of the Pathet Lao.

Due to the landlocked position of Loas, to gain any advantage American troops would have to be committed and the supply problems were too great. The United States abandoned Laos and turned its support of arms and military aid, including aircraft and Special Forces Advisors, to South Vietnam.

At the end of the 1950s, there were few Special Operations Forces. The Army had the Green Berets, and the Navy had their Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT). These elite units were trained to fight and operate behind the lines of a conventional war, specifically in the event of a Russian drive through Europe.

The Navy entered the Vietnam conflict in 1960, when the UDTs delivered small watercraft far up the Mekong River into Laos. In 1961, Naval Advisers started training the Vietnamese UDT. These men were called the Lien Doc Nguoi Nhia (LDNN), roughly translated as the “soldiers that fight under the sea.”

President Kennedy, aware of the situations in Southeast Asia, recognized the need for unconventional warfare and utilized Special Operations as a measure against guerrilla activity. In a speech to Congress in May 1961, Kennedy shared his deep respect of the Green Berets. He announced the government’s plan to put a man on the moon, and, in the same speech, allocated over one hundred million dollars toward the strengthening of the Special Forces in order to expand the strength of the American conventional forces.

Realizing the administration’s favor of the Army’s Green Berets, the Navy needed to determine its role within the Special Forces arena. In March of 1961, the Chief of Naval Operations recommended the establishment of guerrilla and counter-guerrilla units. These units would be able to operate from sea, air or land. This was the beginning the official Navy SEALs. Many SEAL members came from the Navy’s UDT units, who had already gained experience in commando warfare in Korea; however, the UDTs were still necessary to the Navy’s amphibious force.

The first two teams were on opposite coasts: Team Two in Little Creek, Virginia and Team ONE in Coronado, California. The men of the newly formed SEAL Teams were educated in such unconventional areas as hand-to-hand combat, high altitude parachuting, safecracking, demolitions and languages. Among the varied tools and weapons required by the Teams was the AR-15 assault rifle, a new design that evolved into today’s M-16. The SEAL’s attended UDT Replacement training and they spent some time cutting their teeth at a UDT Team. Upon making it to a SEAL Team, they would undergo a three-month SEAL Basic Indoctrination (SBI) training class at Camp Kerry in the Cuyamaca Mountains. After SBI training class, they would enter a platoon and train in platoon tactics (especially for the conflict in Vietnam).

The Pacific Command recognized Vietnam as a potential hot spot for conventional forces. In the beginning of 1962, the UDT started hydrographic surveys and Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) was formed. In March of 1962, SEALs were deployed to Vietnam for the purpose of training South Vietnamese commandos in the same methods they were trained themselves.

In February 1963, operating from USS Weiss, a Naval Hydrographic recon unit from UDT 12 started surveying just south of Da Nang. From the beginning they encountered sniper fire and on 25 March were attacked. The unit managed to escape without any injuries, the survey was considered complete and the Weiss returned to Subic Bay.

By 1963, the Vietnamese LDNN was starting to meet success within their missions. Operating American-provided, Norwegian-built “Nasty” class fast patrol boats out of Da Nang, the LDNN were able to make several raids against North Vietnamese targets. On 31 July, the Nastys were used on a mission to destroy a radio transmitter on the island of Hon Nieu. Using 88mm mortar on the night of 3 August, they shelled the radar site at Cape Vinh Son.

Due to the immense firepower of the 88mm recoilless, the North Vietnamese believed the large guns of an U.S. Naval ship were bombarding them. Under this assumption, NVA gunboats made a daylight attack on the USS Maddox, which was cruising off the North Vietnamese coastline, intercepting radio transmissions. This and a second attack later the same day on the USS Turner Joy came to be known as The Gulf of Tonkin Incident.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident gave the Unites States the legal and political power to justify a stronger involvement in the Vietnam conflict. A bombing of an U.S. Air Base on 30 October 1964 killed five servicemen. Another attack on Christmas Eve hit a U.S. billet in Saigon, killing 2 servicemen. President Lyndon Johnson ordered “tit-for-tat” reprisal: for every attack from the North Vietnamese, American troops would respond in the same manner. The initiation of Operation “Flaming Dart,” which included the American bombing of targets in North Vietnam, placed America in the middle of an all out war.

The CIA began SEAL covert operations in early 1963. At the outset of the war, operations consisted of ambushing supply movements and locating and capturing North Vietnamese officers. Due to poor intelligence information, these operations were not very successful. When the SEALs were given the resources to develop their own intelligence, the information became much more timely and reliable. The SEALs and Special Operations in general started showing an immense success rate, earning their members a great number of citations.

Between 1965 and 1972, there were 46 SEALs killed in Vietnam. On 28 October 1965, Comdr. Robert J. Fay was the first SEAL killed in Vietnam by a mortar round. The first SEAL killed engaged in active combat was Radarman second-class Billy Machen who was killed in a firefight on 16 August 1966. Machen’s body was retrieved with the help of fire support from two helicopters, after the team was ambushed during a daylight patrol. Machen’s death was a hard reality for the SEAL teams.

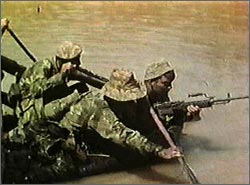

The SEALs were initially deployed in and around Da Nang, training the South in combat diving, demolitions and guerrilla/anti-guerrilla tactics. As the war continued, the SEALs found themselves positioned in the Rung Sat Special Zone where they were to disrupt the enemy supply and troop movements, and into the Mecong Delta to fulfill riverine (fighting on the inland waterways) operations.

The brown water of the Delta provided the foundation for the development of SEAL riverine operations. The SEALs adapted quickly and with deadly results. The braces, inlets and estuaries intermingled and left a broad area for both the North and South to operate. The SEALs and Brown Water Navy Boat Crews made it their job to win this part of the war, impeding as much as possible the movement of troops and supplies coming from the North.

The SEAL teams experienced this war like no others. Combat with the VC was very close and personal. Unlike the conventional warfare methods of firing artillery into a coordinate location, or dropping bombs from thirty thousand feet, the SEALs operated within inches of their targets. SEALs had to kill at short range and respond without hesitation or be killed. Into the late sixties, the SEALs made great headway with this new style of warfare. Theirs were the most effective anti-guerrilla and guerrilla actions in the war.

However, back at home the politics of war were working against the administration. The anti-war protest became much louder by the end of the sixties. The American public began to question this war that was claiming so many of their young men. The anxiety and anger caused by the war began to take its toll and violence erupted at home. National Guard units were sent to college campuses to disperse protesters. The now infamous incident at Kent State that resulted in four fatalities was one of many clashes between protesters and the government.

SEALs continued to make forays into North Vietnam and Loas, and unofficially into Cambodia, controlled by the Studies and Observations Group. The SEALs from Team 2 started a unique deployment of SEAL team members working alone with South Vietnamese Commandos. In 1967, a SEAL unit named Detachment Bravo (Det Bravo) was formed to operate these mixed US/ARVN units, which were called South Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Units (PRU).

In the beginning of 1968, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong orchestrated a major offensive against South Vietnam. Virtually every major city felt the effects of the “Tet Offensive.” The North hoped it would prove to be America’s Dien Bien Phu. They wanted to break the American public’s desire to continue the war. As propaganda the Tet Offensive was successful: America was weary of a war that could not be won, for principles no one was sure of. However, North Vietnam suffered tremendous casualties, and from a purely military standpoint the Tet Offensive was a major disaster to the Communists.

By 1970, the US decided to remove itself from the conflict. Nixon initiated a Plan of Vietnamization, which would return the responsibility of defense back to the South Vietnamese. Conventional forces were being withdrawn, however, operations of the SEALs continued. The SEALS had developed a new base at the tip of the Ca Mau Peninsula and created a floating firebase, now known as Seafloat, by welding together fourteen barges. Accessible from sea, it also provided a landing area for helos.

On 6 June 1972, Lt. Melvin S. Dry was killed when entering the water after jumping from a helicopter at least 35-feet above the surface. Part of an aborted SDV operation to retrieve Prisoners of War, Lt. Dry was the last Navy SEAL killed in the Vietnam conflict. The last SEAL platoon departed Vietnam on 7 December 1971. The last SEAL advisor left Vietnam in March 1973.

The UDTs again saw combat in Vietnam while supporting the Amphibious Ready Groups. When attached to the riverine groups the UDTs conducted operations with river patrol boats and, in many cases, patrolled into the hinterland as well as along the riverbanks and beaches in order to destroy obstacles and bunkers. Additionally, UDT personnel acted as advisors.

On May 1, 1983, all UDTs were re-designated as SEAL Teams or Swimmer Delivery Vehicle Teams (SDVT). SDVTs have since been re-designated SEAL Delivery Vehicle Teams.

Special Boat Units

SBU can also trace their history back to WWII. The Patrol Coastal and Patrol Boat Torpedo are the ancestors of today’s PC and MKV. Motor Torpedo Boat Squadron THREE rescued General Macarthur (and later the Filipino President) from the Philippines after the Japanese invasion and then participated in guerrilla actions until American resistance ended with the fall of Corregidor. PT Boats subsequently participated in most of the campaigns in the Southwest Pacific by conducting and supporting joint/combined reconnaissance, blockade, sabotage, and raiding missions as well as attacking Japanese shore facilities, shipping, and combatants. PT Boats were used in the European Theater beginning in April 1944 to support the OSS in the insertions of espionage and French Resistance personnel and for amphibious landing deception. While there is no direct line between organizations, NSW embracement is predicated on the similarity in craft and mission.

The development of a robust riverine warfare capability during the Vietnam War produced the forerunner of the modern Special Warfare Combatant-craft Crewman. Mobile Support Teams provided combat craft support for SEAL operations, as did Patrol Boat, Riverine (PBR) and Swift Boat sailors. In February 1964, Boat Support Unit ONE was established under Naval Operations Support Group, Pacific to operate the newly reinstated Patrol Torpedo Fast (PTF) program and to operate high-speed craft in support of NSW forces. In late 1964 the first PTFs arrived in Danang, Vietnam. In 1965, Boat Support Squadron ONE began training Patrol Craft Fast crews for Vietnamese coastal patrol and interdiction operations. As the Vietnam mission expanded into the riverine environment, additional craft, tactics, and training evolved for riverine patrol and SEAL support.

SEAL Delivery Vehicle Teams

SDV Teams trace their historical roots to the WWII exploits of Italian and British combat swimmers and wet submersibles. Naval Special Warfare entered the submersible field in the 1960’s when the Coastal Systems Center developed the Mark 7, a free-flooding SDV of the type used today, and the first SDV to be used in the fleet. The Mark 8 and 9 followed in the late 1970’s. Today’s Mark 8 Mod 1 and the Advanced SEAL Delivery System (ASDS), a dry submersible, provide NSW with an unprecedented capability that combines the attributes of clandestine underwater mobility and the combat swimmer.

Post-Vietnam War operations that NSW forces have participated in include URGENT FURY (Grenada 1983); EARNEST WILL (Persian Gulf 1987-1990); JUST CAUSE (Panama 1989-1990); and DESERT SHIELD/DESERT STORM Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti, Liberia, Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom and a host of classified mission around the world. See the Operations content for insight into some of these more interesting operations. See the “Take the Challenge” section for information on the path to becoming one of these elite warriors.